Orissa Killer Cyclone 1999: Recollections & Some Lessons for Phailin

By Saswat Pattanayak

New York, October 13, 2013

Cyclone Phailin is not over yet, and Orissa is not all about Bhubaneswar. If lessons be learnt from 1999, there’s an enormous amount of work to be done, beginning with the administration ending its premature jubilation. Even as this cyclone did not prove to be as catastrophic as the ’99 one, we must not undermine the challenges that are ahead of us. Evacuation is not enough, rehabilitation is the key. Farmers, fishers and the poor in the vulnerable coastal belts devoid of ecological balances, wrought upon them through corporate greed – are the sections of population that will be the worst sufferers. 500,000 hectares of crops have been damaged and the already impoverished state of Orissa has been relegated further down.

I am sharing below, my journey as a reporter during the 1999 “super cyclone” when the team of Asian Age (and later on, Hindustan Times) covered it extensively. Some of these recollections have pure nostalgic values, but many are pointers to what may lie ahead.

1999 – the year of the super cyclone – was the year I started my professional career in journalism. After my studies at IIMC, I left Delhi and my short stint there with Economic Times, to return to my hometown, Bhubaneswar. And, within a couple of months, the first major story of my life was to welcome me at the Asian Age office.

And what a remarkable welcome it was to be. I started with creating layouts and subbing copies at the desk. And even as I actually quite enjoyed QuarkXpress, I wanted to be on the field as well. I wanted to bunk my afternoon classes at the university and do some reports. Besides, I had gained some field experiences investigating “dropsy scare” while at Economic Times. So I could not wait to interview people and address various issues affecting Orissa.

But my appointment with Asian Age was as a sub-editor, not as a reporter. Our office was located in a forbidden zone, at an “industrial complex” far away from the city; resembling a ghost town. And I used to return home around 3am every night after “releasing” the paper and smelling the first copy by the printer. Along with two of my colleagues at the desk and three colleagues from the I.T. department, we had among ourselves formed a solidarity network. We were fairly young a team. At 22, I was possibly the youngest. We felt overworked, underpaid, untimely hungry, and too damn tired, every night. And there was no working around that…

My resident editor, however, wanted to give me a chance to work as a reporter as well, since I insisted I could do both the field and the desk jobs. And the breakthrough came when I was told I could cover the “weather” beat. This first seemed hilarious to me, since even as a reader, I never read a weather report in a newspaper. For us Oriyas, weather could be predicted by looking at the sky. And I had no idea where the local Met office was, anyway. It was quite telling, that a beat was being assigned to a reporter who had no idea where the experts in his/her field worked!

I still took up the offer and wondered if I would ever get a byline for a weather story in an otherwise quaint climate of Bhubaneswar. Maybe I needed to wait for the next summer when the sunstrokes would make some mundane but required news items. Reporters can be ruthless about the news factors, and I was no exception. As a sub-editor, I was already aware of what made “hard news”. It had to involve deaths; in fact, not just deaths, shocking deaths. We were professional sadists. More the mayhem, greater the glee. A train accident made the font size go bigger. An assassination led to multiple column stories. And the more local a tragedy, the more space allotted to a reporter. Alas! In Bhubaneswar, there was no such hard news. A few press conferences here and there. And some quite predictable and boring political shuffles.

In October, when the “depression” set in by neighboring Andhra Pradesh, it was the first hour of alert. For me, something was brewing, but I was still not sure of its scope. Our Met department narratives were unconvincing during the day and when I thought of covering the story for the front page, it was past the office hours that evening. So I set out to the only cyber cafe in the town, ‘Message Cafe’, owned and operated by Ajay Raut, a young man of extraordinary optimism. Ajay bhai greeted me and assured every support possible to make my story a breaking one. Purely an online investigation, at slow but consistent dial-up connection, we together gathered an array of documents and screenshots of weather reports that I was to carry with me back to my office that October evening of 1999.

My byline finally featured on the first page of the newspaper. My resident editor Soumyajit Pattnaik, a dynamic new entrant into Orissa media circle from his previous stint at the Pioneer in Delhi, praised my efforts. I soon discovered he and I shared a common passion for the new media and how internet was impacting the newsroom.

I compiled an “All you wanted to know” piece on cyclone for the interested readers. It was the first of its kind in local journalism and attracted due attention.

When the first tropical cyclone arrived, we could do all the analysis, but it still claimed 61 human lives. It was quite an alarming sign to what was in store the next month. I wrote a front page piece on what results in such unpredictable a cyclone and what Coriolis Effect was. But what also occurred to me was how 61 lives were lost and yet the central government was least bothered. There was hardly any funding coming in to the state and the political apathy was quite telling.

Coriolis Effect results in cyclones – Saswat Pattanayak / The Asian Age

On October 22, I wrote a story detailing how Delhi’s help vis-a-vis the Calamity Relief Fund was merely a straw in the wind for the affected in Orissa. The primary reason for the thousands of lives to be lost in the subsequent super cyclone was primarily rooted in this lack of financial support for the state.

Calamity Relief Fund – Saswat Pattanayak / The Asian Age

Back in Orissa, in apprehension of the approaching super cyclone, “black-marketing” remained in full force. I focused on the most essential of commodities – kerosene oil which was being sold at seven times its normal rate. I cited legal precedents via the newspaper to prompt the state government to take action and to stay alert on future abuses of the laws (which surely happened).

Without adequate central government funding, without any check on corrupt practices by the trading class and without any lessons learnt from the tropical cyclone that had already claimed 61 lives, Bhubaneswar and the coastal belt of Orissa awaited what our newsroom declared on its first edition following the most disastrous cyclone to have hit Orissa – Apocalypse.

Forming of Depression: Saswat Pattanayak / The Asian Age

The super cyclone – that I termed later on as “Killer Cyclone” because I was not comfortable with the glorification of this disaster – had its worst manifestations on October 29, 1999. It was so ferocious, and so catastrophic and so unbelievable, that nothing compared to it in recent history.

As young journalists, we were all excited beyond measure and wanted to cover it in the best possible manners. But the physical limitations were overpowering our will. On the one hand there was no electricity and no one had a clue when it was going to be restored. Electricity in Orissa those days as such was a privilege during regular times! On the other hand, the city we knew to be filled with greenery was now ravaged beyond repair. Literally hundreds of thousands of trees were uprooted. Highways were blocked, let alone the streets and roads. The city entirely unprepared for this disaster became a city without any law and order. Forget about the nights, even the days were no longer safe for anyone. Not just from the want of food materials, but also from electric wires. There was no question of taking a car out on the roads. The only vehicles such as small two-wheelers (Luna mopeds!) could be lifted up if needed to cross over tree logs that were heavier than most bikes. Or, of course, the good old bicycles were the best alternatives.

Our office as noted earlier, was in a ghost town – Mancheswar Industrial Estate – whose streets were dark even during normal evening hours. Following the cyclone, there was no way to navigate that path, even as all of us colleagues were raring to get out and inform the public about the extent of onslaughts.

Saswat Pattanayak, in 1999, the morning after super cyclone.

My friend and senior sub-editor Pranesh Dey dragged his bike to my house within hours of the cyclone ending its exploits. My father, a veteran investigative journalist himself, was left speechless and astonished. As protective as he was, there was no way I was allowed to venture out in this climate. Following conversations between my parents, finally, my father relented, and Pranesh bhai and I went around the city to inspect the extent of damages. It was a spectacle we would never forget.

But we could not venture much, as the roads were so filled with trees that it could literally take months to go around all corners of this small town. All public service utilities were shut down, and so were the media. Without power, it was impossible to imagine that any newspaper office would resume anytime soon.

We had different plans though. Much to our great delight, our management and editorial team decided that we would be the first and only newspaper in Bhubaneswar to resume operations under these conditions. Instead of coming in around the evening hours, we decided to work afternoon through evening. And using generator to pull electricity. An expensive proposition, but what a thrilling one!!!

The Paper: Utkal Age Team, 1999.

There was obviously no internet and so no Delhi edition, no FTP connections, and no Mr. M.J. Akbar to know about this edition, let alone admonish us on failing on the style sheet. Our underground team comprised our resident editor Soumyajit Pattnaik, utterly brilliant chief of desk, V. Kaushik Kumar, creative superhero and subeditor Pranesh Dey, reporters Elisa Patnaik, Sandeep Mishra, Akshaya Sahoo, photographer Ashok Panda, sub editors Sanjay Nath, Alaka Sahani and Saswat Pattanayak – together, we worked on the greatest layout we had ever created for the newspaper. And since this much smaller edition was literally a team work, we decided against bylines for anyone. It was the first paper that was produced entirely at the desk. We worked at record speed. And we upped the headline font to defy all rules. And so excited we were – amidst the miserable conditions just outside the office building, which we had managed to reach with immense difficulties.

By the time the paper was released – and in small numbers of prints that day – it had grown dark. We were fearing for not just the occasional “highway bandits”, but also for the wildlife animals on the loose. Snakes were a major concern where our office was. And it was a long long night back home. Getting off from our bikes and bicycles and jumping over the trees and live electric wires, it was an adventure we would never forget.

Amidst my thrilling adventures, I had not entirely forgotten how worried my family would be. Knowing my father, and without telephone connectivity, I was especially concerned. And just as I had guessed, on my way back from work, I found him in the middle of the road with a torchlight in his hand, searching for me on a bicycle! I had never seen him in such a helpless and worried state as that night. My colleagues were also amazed to see him so concerned, and finally, we all happily returned home.

Happiness was less for the safe return as it was because of the anticipation for the next morning. In the wee hours, Pranesh bhai and I headed to the Rajmahal Square to celebrate the arrival of the only newspaper that detailed the cyclone. In fact, the only newspaper that was published the night before! What a moment of joy and pride it was for us! And while deeply cognizant of what terrible times awaited the sufferers.

It was almost a surreal moment that made us take a pause and interrogate ourselves. The more tragic a news was, the more fulfilled we felt as journalists. Between our roles as disseminators of news, we were clearly refusing to recognize our privileges of having been alive, been doing well despite all the darings, and more importantly, celebrating the journalism component of it instead of joining the statewide mourning for the loss of lives.

And at some point thereafter, moving away from the celebrations, we focused on our duties as informers, investigators and potential agitators. Something simply was not going well. We were struck by the thousands who were rendered homeless, who should not have been in that state, to begin with. The worst sufferers were the people who were homeless even before the cyclone ravaged the state. The next day I had a front page “anchor” story that highlighted the good amidst the ugly, the reconstruction amidst the destructions, and the helping hands of volunteers that were attempting to overpower the tight grips of the bureaucrats. And I wrote:

“The whole populace has not been left helpless. And take heart, the providers of silver lining in a cloud of grey for the cyclone-hit ones, do not have political affiliations and are in no mood to earn publicity. In tempestuous times like these, if solidarity ought to be maintained, the students of the city are definitely doing their bit to strengthen it.”

Homeless in Orissa: Saswat Pattanayak / The Asian Age

The idea was to bring a smile and some hope. And to use journalism as an empowering vehicle. We noticed that it was never truer than then. Highlighting the ways people were positively contributing to rehabilitation efforts was one of the ways I thought we could inspire more into emulating them. From students to the Red Cross, we covered every effort, no matter how small or big. For it was one thing to write about scandals affecting an individual or accidents involving a few, but quite another to write about the disasters awaiting millions of people, majority of whom being poor.

People of Orissa were about to suffer for the next decade due to the 1999 cyclone. It’s impacts were not immediately going to be known. They could only be estimated. Restoration of the green vegetation was to take at least another ten years, and we highlighted the environmental impacts of the disaster and the need to rapidly restore the greenery.

“Oil is not Well” ran the slug for my ongoing stories on the kerosene mismanagement. Fair price shops were conveniently shut down and the government did not do a thing about it. Hoarding of kerosene continued unabated well into the second week since the cyclone. Police force was not deployed around the areas of conflicts where endless queues were observed for a litre of kerosene.

Oil is Not Well: Saswat Pattanayak || The Asian Age

Kerosene crisis and mismanagement: Saswat Pattanayak || The Asian Age

The courage of Oriyas in fighting against odds, injustices and climatic challenges has been indomitable. Despite the tremendous after-effects of super cyclone, the city of Bhubaneswar had resolved to resume its operations. The city was still engulfed in darkness, electric poles were still twisted out of shape, educational institutions were closed for indefinite periods and majority of people still refused to get out of their homes. But on the other hand, the community of volunteers was ready to police the city by the nights, young students lined up to pack relief materials – food and medicines – for the needy. When our editor was away to a meeting in Delhi, I wrote an entirely unplanned piece declaring that we could withstand it all –

“In turbulent times as these, not everything goes inimical. Observable vicarious emotions among the city folks was previously even unheard of. From clearing lanes to lifting buckets of water, the city fraternity is helping getting back the vivacious look of the city. It may take a few more years to make it clean and green once more, but the wave of solidarity being displayed has certainly overpowered the wave of cyclone that had swept the city off its dreams.”

Bhubaneswar Fights the Odds: Saswat Pattanayak || The Asian Age

While the battle was ongoing against the impacts, it still puzzled us as to why our Met office had failed at predicting the enormity beforehand. Continuing from the Coriolis effect story, I ran a piece exploring the reasons why we failed to comprehend the potential the second time.

Why Cyclone Predictions Failed: Saswat Pattanayak || The Asian Age

Deadlier catacysm predicted: Saswat Pattanayak // The Asian Age

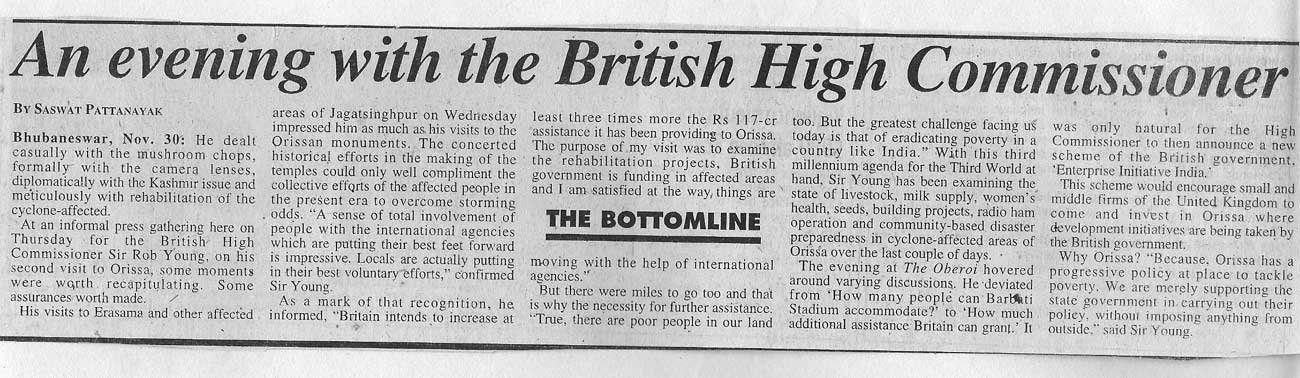

Not only had we failed to apprehend the weather, we also failed to apprehend the corruptions. Hundreds of NGOs lined up to cash in on the crisis. Tata Sumo appeared as the symbol of non-profit sector that immensely profited from the tragedy. I ran a few stories highlighting the corruption in the NGO sector which invited a lot of ire. And when I broke the story on Red Cross, the smaller fish on the ocean of misappropriated philanthropy finally stopped complaining. But when Red Cross failed, we knew most of the relief efforts were going to also subsume under waves of corruption. From the British High Commissioner to the Bollywood, everyone visited Orissa with a “human face” to promise help that never quite was delivered.

Red Cross Corruption Scandal: Saswat Pattanayak || The Asian Age

British High Commissioner Sir Rob Young : Saswat Pattanayak || The Asian Age

My fellow colleagues Sandeep Mishra and Akshaya Sahoo broke many a stories detailing bureaucratic corruptions at various levels. Starvation deaths, expired medicines, decaying bodies and epidemic threats were reported from all over the coastal belt, especially from Erasama, Jagatsinghpur. I visited Jagatsinghpur during the third week of November and during my investigation, noticed that despite the desperate needs and allotments, not a single blanket had reached the villagers.

In my interviews with the affected in Jagatsinghpur, I found out that there was enormous amount of bureaucratic mishandling. In place of the required 767,181 blankets, there was, zero. A villager said, “Every time a team of babus arrive in Manijanga, we make out way there, but are disappointed as many times. We get nothing more than 500 gm of rice. When do not get even chuda (flattened rice) as required, who will give us blankets to cover our bodies from shivering cold in roofless nights?”

Jagatsinghpur- Polythene Scam: Saswat Pattanayak || The Asian Age

When I decided to visit Paradip and Jagatsinghpur, my father insisted on accompanying. He admitted of not having seen anything like this on the way. Everywhere we went, stinks followed, and approached. Of rotten crops, dead animals, unattended bodies.

Jagatsinghpur Blankets Scam: Saswat Pattanayak || The Asian Age

There were at least two major corruptions during Orissa super cyclone. If one was the blanket, the other was polythene supply. Whereas the government continued to claim that sufficient polythene rolls had arrived, the local officials claimed otherwise. And during another investigation in Jagatsinghpur I found out that the actual rolls received were far less than the claim was. In Paradip, for instance, there was not a single polythene roll yet. In the entire region, as against the requirement of 51,144, there was a supply of only 4,482 rolls.

Two months subsequent to that, when I made another follow-up, I reached the conclusion that not much had changed in Jagatsinghpur. The worst affected population in a coastal region comprised the fishermen and women, and the government had miserably failed at taking care of their needs to build up boats so they could resume their works.

Jagatsinghpur – Fishermen Boat Scam: Saswat Pattanayak || The Asian Age

Killer cyclone of 1999 left behind not just a trail of devastations that needed several years of honest, dedicated governance – which Orissa sorely lacked, it also left behind memories of courageous battles with the nature’s ravaging plans. The aftereffects were almost indistinguishable from the catastrophe itself. Our state government was mired by corruptions – political and bureaucratic, and the global media had even failed to report the cyclone beyond a single column.

Orissa Cyclone Aftermath Analysis: Saswat Pattanayak || The Asian Age

The 1999 killer cyclone had caused the deaths of nearly 10,000 human beings, killing 400,000 livestock, impacting the lives of 12 million people, 7,921 villages, damaging 800,000 houses, 1.67 million hectares of agricultural lands and rendering 400 villages inaccessible as of May, 2000.

That is around the time when I was approached by the eminent political scientist of the state and a critical commentator whom I deeply admire, Professor Biswaranjan, to write a book on the entire bureaucratic fiasco, the ongoing courageous battles and the difficult challenges that lie ahead for Orissa. And we both co-authored the very first book exclusively devoted to what we called the Killer Cyclone of 1999: “Knock and the Rise”. Dr. Bibudharanjan from Puri helped publish it through Insight, and the new Chief Minister of Orissa Naveen Patnaik inaugurated the book.

Orissa Chief Minister Naveen Patnaik releasing the book on Orissa Supercyclone, Knock and the Rise, co-authored by Adhyapak Biswaranjan and Saswat Pattanayak.

In the meantime, Asian Age decided to exit from Orissa and shut down Utkal Age. And around the same time, Hindustan Times decided to make its entry into Orissa. I was interviewed by a panel from Delhi, and was initially recommended to work in Kolkata. I wanted to stay back in Bhubaneswar, however, for two primary reasons – one, I was falling in love in the middle of the storm, with my friend Amrita Misra – and there was simply no working around that! And two, I also wanted to follow-up more on the cyclone aftermath, and my going away to Kolkata was not going to be useful. Everything went in my favor, as both Amrita and I started working together for HT.

While following up on the cyclone, among other stories, I explored how there was something that the people grappled with and which escaped attention of the media: intense trauma/PTSD. Even after 16 months, the psychological crisis was left unresolved by a state clearly ill-equipped to address them. The most vulnerable people during any disaster are the ones who are left behind in the race to make sense of their lives. Even while the relief materials were being air-dropped, we used to witness the most able-bodied men ending up receiving the most for themselves, leaving behind women, children, and the ones on the fringes, the ones with physical and mental disabilities. For the following story, I interviewed Prof. J.P. Das (Alberta) and Prof. R.N. Kanungo (McGill) to explore why the cyclone was nowhere yet leaving Orissa. This was the first time that PTSD started getting discussed in the media, and we gained immensely from the expertise and pioneering works of Ms. Kasturi Mohapatra of Open Learning Systems, Bhubaneswar.

Cyclone – Trauma and PTSD: Saswat Pattanayak || The Hindustan Times

Before joining Ranchi as part of the new Hindustan Times edition there the following year, I did a last report on the cyclone, a nostalgic piece on “How green was my home”…Never could I allow myself to imagine that Orissa may have to endure a killer cyclone of that ferocity ever again.

Bhubaneswar, post-cyclone. 2001: Saswat Pattanayak || The Hindustan Times

With Cyclone Phailin now leaving behind a trail of destruction, it occurs to me that it’s not all over yet. With the loss of greenery from the ’99 cyclone and the subsequent deforestations caused by POSCO and corporate greed, the journey is only going to be uphill and more difficult. Certainly the lives lost this time are going to be far less, and surely the capital city of Bhubaneswar has been spared, but this is too early to say about the extent of actual damages, and too naive to assume the final estimate, in the entire region, beyond the city. I shall keep a watch from afar on the reporting in the rural Orissa and of any possible repetitions of “man-made” mistakes from 1999 days. Thirteen years ago, when Naveen Patnaik had received “Knock and the Rise” the first time, he had promised to take a look at the pointers therein, and I – along with Adhyapak Biswaranjan would be sure to follow up on his promise. That book is out of print, but thankfully, my father has reproduced portions of it for availability to the administrationand Orissamatters.com will remain alert against any falsified claims that may be made by the administration in the coming months/years.

These days when I shut down my apartment’s glass windows in New York City – despite Hurricane Sandy, I feel much more protected, lot more privileged and far less adventurous. And very much alive. Not all of us are often fortunate to withstand nature’s wraths. But when we do, it is only because we have had the privilege, not because we take anything for granted. The lesson to learn and to implement is that we need to redistribute that privilege, to learn from historical blunders. In such trying times during the aftermath of Phailin, I can only advise, through sharing of my experiences, that in future months, we must do everything possible to raise awareness, consciousness and efforts so that people do not continue to line up for petrol and kerosene and sugar – something that we already witnessed in the week before Phailin approached. That, the medicines they receive as relief materials are not expired. That, they are not in want of blankets and polythene sheets as the winter will position itself with the floods in coming months. That the starvation deaths do not continue to rise (or, be denied) in the pretext of the cyclonic aftermath. That, the massive evacuation efforts alone do not count towards the success, until all the evacuated people have been rehabilitated adequately. That, those of us who can access Internet suddenly do not write away the plights of those who still cannot convey their needs, to those already congratulating each other, in power.